Early forms of exclusion

Sinti and Roma have been mentioned in documents in almost every country of Europe since the early 15th century. Initially, the minority enjoyed the protection of German kings and sovereign princes. But in the late 15th century, late-medieval society underwent a phase of political and social upheaval as it transitioned to the early modern era, and the Sinti and Roma became increasingly marginalised and persecuted in the process. In 1498 the Reichstag meeting in Freiburg declared ‘gypsies’ to be ‘vogelfrei’, i.e. ‘free game’ or outlaws, as they were accused of being spies for Turkey. This meant they could be killed with impunity.

Despite a policy of displacement and expulsion that was strictly enforced by the sovereigns of newly established territorial states, the Sinti and Roma found ways of surviving and spotted economic niches. Social and economic relations of many kinds were established between minority and majority society. Individual members of the minority succeeded in rising up the ranks of the military or sovereign public policy (Policey), even attaining officer ranks. But the emergence of a nationalism predicated on völkisch or ethnic aspects meant that such opportunities for advancement were slowly but surely closed off.

01.1 | Since the 16th century, the policy implemented by territorial lords had been aimed at keeping ‘gypsies’ far removed from their territories, along with other poor, marginalised populations outside of estatist society. As ‘masterless groups’ they enjoyed no rights and no protection. There is a wealth of documented evidence that countless exclusion orders and […]

01.1

01.2 | Since the 16th century, the policy implemented by territorial lords had been aimed at keeping ‘gypsies’ far removed from their territories, along with other poor, marginalised populations outside of estatist society. As ‘masterless groups’ they enjoyed no rights and no protection. There is a wealth of documented evidence that countless exclusion orders and […]

01.2

02 | In this edict from 1726, Frederick II, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, informed his subjects of their duties towards the patrolling militias charged with driving ‘beggars, vagrants, gypsies, and all other suspect rabble’ from his lands. These ‘Streiffungen’ – i.e. organised hunts or forays against people regarded as foreign and undesirable by the authorities – […]

02

03 | In the 18th century in particular, prohibition signs aimed at ‘gypsies’ were set up at border crossings throughout the empire as conspicuous warnings designed to deter. They were a drastic illustration of the sort of draconian punishments that would be meted out to ‘gypsies’ should they unlawfully trespass on the relevant territory. This […]

03

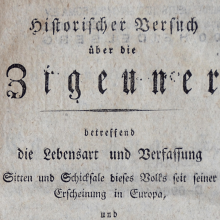

04 | The Göttingen professor Heinrich Moritz Gottlieb Grellmann, an Enlightenment historian, was the founder of modern ‘gypsy research’. The first edition of his book ‘Historischer Versuch über die Zigeuner’ [‘Historical dissertation on the gypsies’] was published in 1783 and subsequently translated into numerous languages; it is widely regarded as seminal. Grellmann regarded ‘gypsies’ as […]

04